Renewing Federalism: a different approach to tertiary education funding

A major imbalance exists in Australia’s tertiary education system. Left unaddressed it will lead to growing disparities in funding between higher education and vocational education and training, distort student choices and create an imbalance in skills in the Australian labour market.

An effective tertiary education system would comprise a range of high quality courses and providers operating across the vocational education and training (VET) and higher education sectors under an equitable funding system.

What would an effective funding system look like?

An effective tertiary education funding system should have three main features:

public subsidies that balance public and private benefits, course costs and the circumstances of individual students

private contributions supported by income contingent student loans that ensure that students only pay when they start to get personal benefits

student income support targeted to the needs and circumstances of individual students.

There is already great diversity of courses and providers across the Australian tertiary education system with growing and better connections between the sectors. The Commonwealth also operates a consistent and comprehensive student income support system for tertiary education students.

But the potential of this system is undermined by growing divergence in how, and at what levels, VET and higher education are funded, and how, and at what level, the states fund their VET systems.

The nature of the problem lies in the Federal/state divide

This divergence in funding levels and models occurs because of the way higher education and VET are funded by the Commonwealth and the states.

The Commonwealth has full responsibility for funding higher education providers. It funds them through public subsidies supplemented by student fees. These fees are paid to providers either directly by students, or by the Commonwealth on their behalf through an income contingent loan. Student fees are regulated by the Commonwealth, but this could change if the government’s Higher Education Bill passes.

The states have full responsibility for funding VET providers. VET student fees are regulated in some states and deregulated in others. However only VET students in Diploma, Advanced Diploma and a few Certificate IV courses have access to the Commonwealth’s income contingent loans schemes. Other students have to pay their fees upfront.

The major flaw in the funding system is that VET funding is a shared responsibility between the Commonwealth and state governments. The Commonwealth contributes to VET provider funding through agreements with each state and territory. These agreements were designed to provide a sustainable base for VET funding and VET enrolments but which have now broken down.

Most states don’t have the capacity or the will to make VET funding a priority. Victoria is the notable exception. VET fees are increasing but most VET students can’t access income contingent loans. They also generally have less capacity to pay than higher education students given a larger proportion of VET students are from low socio-economic backgrounds.

As a consequence public investment in VET has plateaued since 2011 and the future VET funding outlook is even bleaker. The Commonwealth has reduced its funding for the VET agreements with the states from 2017-18.

The funding gap in tertiary education will widen

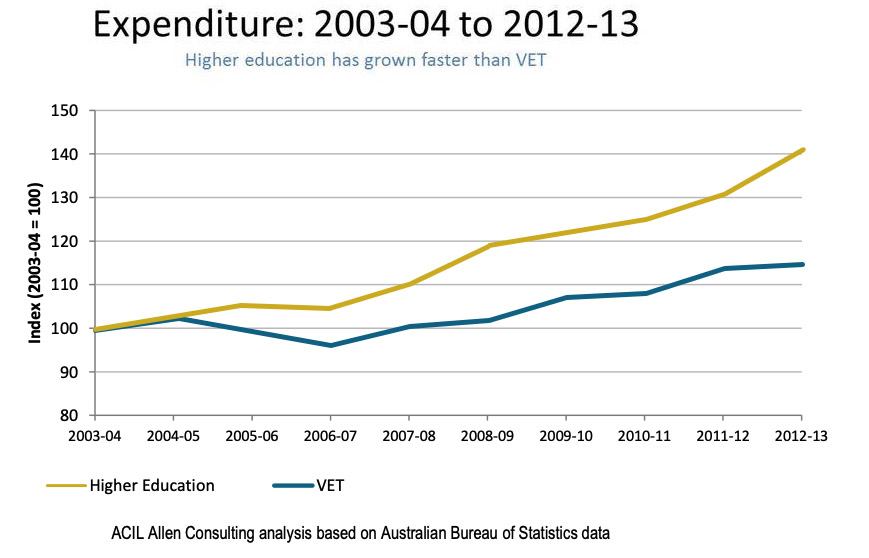

The major gap between investment in higher education and VET - which has always existed - has widened significantly in recent years as the following graph shows.

Graph text alternative:

Graph comparing indexed expenditure on higher education and VET from 2003-2004 to 2012-2013. The data shows that expenditure on higher education has grown faster during that time than expenditure on VET.

Unsurprisingly VET enrolments decreased by 3.4% between 2012 and 2013.

While the balance between public and private funding for higher education will change with budget cuts and fee deregulation, the growth trajectory in higher education funding will increase even if universities set fees at minimum levels required to offset budget cuts.

As a consequence the gap between investment in VET and higher education is likely to widen potentially leading to distortions in enrolments in the sectors, with declining quality and outcomes in VET.

VET is a prime candidate for reform in the federation, and reform has been attempted in the past. In 1992 the Commonwealth offered to assume full responsibility for VET funding from the states. The now dysfunctional shared funding model emerged as a compromise.

Various reviews since then have proposed that either the Commonwealth or the states should take full responsibility for VET funding based on the principle that a single level of government should have responsibility and accountability for specific areas of service delivery.

What are the alternatives?

A full reallocation of responsibility for VET from one level of government to the other is unlikely.

Perhaps its time for a different approach, based around tertiary education entitlement. The Commonwealth could extend the established higher education model of consistent public subsidies, student contributions and income contingent loans into VET by negotiating an agreed per student subsidy level with the states, leaving the states or institutions to set fee levels.

Alternatively the Commonwealth could negotiate a one-off transfer of VET funding from the states for agreed student cohorts (for example school leavers) and provide ongoing funding of an entitlement in both VET and higher education. The states could provide subsidies for student places in VET in areas of state priorities.

Different ways of thinking about the roles of the Commonwealth and the states in tertiary education are needed if we are to have a balanced and fair system across higher and vocational education.

This article was originally published in The Conversation, 18 September 2014.

Read the original article.