Your ATAR isn’t the only thing universities are looking at

Only a quarter of undergraduate university admissions for domestic students are made on the basis of an ATAR (Australian Tertiary Admission Rank), according to a new discussion paper from Victoria University’s Mitchell Institute.

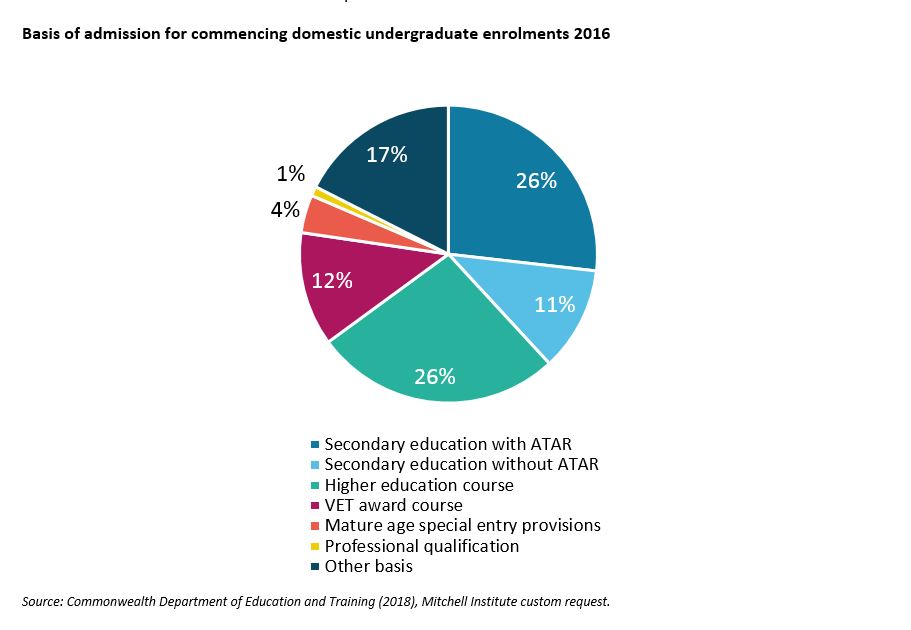

The paper highlights a growing disconnect between the role the ATAR plays in schools and universities. In 2016, only 26% of domestic undergraduate university admissions were made on the basis of secondary education with an ATAR – down from 31% in 2014.

This would surprise many young people, as it seems at odds with the message reinforced by many schools, families and the media – that the ATAR is everything.

The ATAR is a commonly used criterion for admission to undergraduate study. It is a nationally comparable percentile rank (given between 0 and 99.95 in increments of 0.5) signifying a student’s position relative to other students.

The ATAR, and the state-based ranking systems that preceded it, were designed to facilitate transparent and efficient selection to limited places in higher education. But the ranking has arguably taken on a life of its own. As Chief Scientist Alan Finkel said recently:

We…know the ATAR is a tool. Students treat the ATAR as the goal.

Multiple pathways to entry

The introduction of the demand driven system in 2012 saw a removal of caps on Commonwealth supported undergraduate university places. Australia’s tertiary education sector has seen immense change since then, growing significantly and becoming more diverse and accessible.

Commencing higher education students rose from around 410,000 in 2007 to nearly 600,000 by 2016. The 2017 Commonwealth decision to freeze the funding provided for Commonwealth supported undergraduate students may have some impact on this, although the extent is not yet known.

Regardless, we now have a flexible system, with multiple pathways to entry and more students applying directly to institutions.

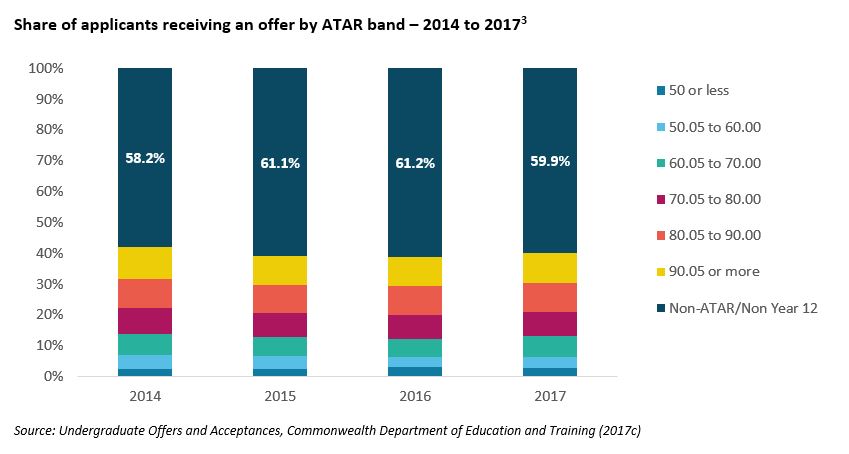

Our new paper highlights that in 2017, around 60% of domestic undergraduate university offers were reported as non-ATAR or non-Year 12, showing a diversity of pathways to higher education.

Graph text alternative:

Graph showing the share of undergraduate applicants who received an offer from 2014 to 2017, by ATAR band. The data shows that the majority of offers (around 60% in each year) were reported as non-ATAR or non-Year 12.

Non-ATAR admissions can be made on the basis of secondary school results (without ATAR), previous higher education or VET study, professional qualifications, and mature age or equity entry pathways.

Graph text alternative:

Pie chart showing the basis of admission for commencing domestic undergraduate enrolments in 2016: Secondary education without ATAR - 26%; Secondary education without ATAR - 11%; Higher education course - 26%; VET award course - 12%; Mature age special entry provisions - 4%; Professional qualification - 1%; Other basis - 17%.

Universities are also turning to a number of alternative entry mechanisms including aptitude tests, entrance exams and interviews. In 2017, 69% of undergraduate offers in the fields of health and education were non-ATAR/non-Year 12. For nursing, this was 78%.

Schools still strongly focused on ATAR

Much of senior secondary schooling is still strongly focused on the ATAR, an emphasis that can result in unintended consequences.

A significant number of final year students report alarmingly high levels of stress and anxiety as a result of study pressures.

Students may choose subjects they think will maximise their ATAR over pursuing talents and interests. It also distorts student choice about which pathway to pursue. Some students see high cut-off scores as an indication of higher course quality, and similarly, that to enrol in courses with cut-offs lower than their ATAR would be a “waste” of their scores.

Symptom of a larger problem

The reality is the ATAR is only one element of a larger and more complex picture. Many of the problems we associate with the ATAR are really symptoms of a broader disjuncture in the way we think about education and training pathways for young people.

To move forward, any reforms need to acknowledge that secondary and tertiary education form part of one ongoing learning pathway.

In education policy there is broad consensus on a number of high level goals – that education should:

- Develop the foundation skills and broader capabilities required to succeed in a changing world,

- support effective transitions from school to post-school life, and

- enable more school leavers to participate in tertiary study or training.

Yet our means of measuring success and facilitating access often seem at odds with these. This includes the ATAR.

The ATAR presents a challenging dilemma – it needs to measure and mark individual and school achievement, filter and sort applicants into appropriate pathways, and facilitate equity of access and equality of educational opportunity.

But given the changing role and purpose of both school and tertiary education, it’s timely to revisit how we facilitate young people’s pathways at this critical stage.

Collectively, governments, students and families are investing more than ever in education and training in Australia.

There is a broad public benefit to ensuring this investment is spent wisely, and that we have the right framework in place to ensure as many students as possible make a good transition from schooling to the next steps in their lives.

It’s time to assess the ATAR and ask whether it helps or hinders us in achieving our shared education goals.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.